Well, this is going to be my final post on this CSC148 courSe LOG (SLOG) and I’m only now realizing how difficult a task it’s going to be to sum up this semester.

As the semester wore on, I began to understand that learning a new language is really not as hard as it seemed, and that the core functioning of most OOPs is the same, regardless of the language. Indeed, my past experience in Java helped me a great deal in many parts of the course, from understanding to

recursion to linked list, BST.

The exercises and labs too, I felt, were excellent. For the first half of the semester, we got a weekly exercise to complete, which forced me to review my lecture notes and concepts, helping me to perform better in the course. Though they were oftentimes challenging, I feel all of us could have benefitted from some more exercises in the second half of the semester. The labs were also highly educational for two reasons: (1) I worked with two other people, and we continuously helped each other and this shored up my knowledge, and (2) my TA, Amirali, was excellent because he always gave us a different perspective on the problem and helped us think in new, creative ways.(Even though the labs are interrunpted by the strike. )

As of this course, i definitely enjoyed this course, it was incredibly awesome, special thanks to our Extremely Talented Prof Danny Hopefully, i will be able to do well in the exam(Fingers Crossed).

CSC148 Slog

Sunday, March 29, 2015

Revisiting a previous slog

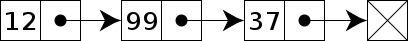

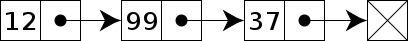

This week, we are asked to revisit a previous slog and write our opinions about it. I chose to go back to post #8, which basically talked about the linked list and BST. In this post, I want to say more about linked list.

In my classmate's post (http://adamosslog.blogspot.ca/), he wrote that " it is useful to have a variable that keeps track of the node that was "visited" just before the current node, so that you can do things like delete the current node by connecting the previous node to one just after the current. ". I agree with his idea. It is very important to keep track of the node; otherwise I have to keep finding the node, which is very inefficient.

Moreover, I realized that linked list is very different from regular list object. Basically the class allows us to create objects with two instance names: value refers to some object (of any class) but next should either refer to an object constructed from the LN class or refer to None (its default value). Linked list has shorter running time than regular list.

In general:

In my classmate's post (http://adamosslog.blogspot.ca/), he wrote that " it is useful to have a variable that keeps track of the node that was "visited" just before the current node, so that you can do things like delete the current node by connecting the previous node to one just after the current. ". I agree with his idea. It is very important to keep track of the node; otherwise I have to keep finding the node, which is very inefficient.

Moreover, I realized that linked list is very different from regular list object. Basically the class allows us to create objects with two instance names: value refers to some object (of any class) but next should either refer to an object constructed from the LN class or refer to None (its default value). Linked list has shorter running time than regular list.

In general:

(1) x stores a reference to the first LN object

(2) x.value stores a reference to the int object 5

(3) x.next stores a reference to the second LN object

(4) x.next.value stores a reference to the int object 3 in this second LN

object

(5) x.next.next stores a reference to the third LN object

(4) x.next.next.value stores a reference to the int object 8 in this third

LN object

Sunday, March 15, 2015

Impression about week 9

Part1: Deletion in BST

This week in lecture we talked more about binary trees, specifically binary search trees. A binary search tree (BST) is similar to the binary tree I talked about two posts ago, except it has the extra condition that the data in the left subtree is less than the data in the root, which in turn is less than the data in the right subtree. This makes searching through the tree much more efficient, because we can use a binary search algorithm instead of a linear search algorithm. Recalling some information from CSC165, we know that binary search has runtime O(log n) whereas linear search takes O(n)–Binary search is much better, because the BST is already sorted, so it can ignore approximately half of the values, because they are all smaller/bigger than the value being searched for.

We also talked about deleting an element in a BST. To do this, we made a delete method in our BST class that simply calls a module-level function called _delete. If my understanding of wrapper classes from last week is correct, BST class function is acting as a wrapper for the module-level delete function, which does most of the work. The module-level function has many cases to deal with. It is given a node in a BST and data to delete. If the node is not None, it can look for the data in the left subtree if the data is less than the node’s data, and the right subtree if it is greater, using the definition of a binary search tree. It then uses recursion to get down to a base case, where the node’s data is equal to the data being searched for. It returns a new tree with the appropriate data deleted.

Part2: Term Test 2

Term test 2 was held on Wednesday. Preparing for the test, I concentrated on lab exercises. I redid all the lab exercises and timed my self.

I was very happy that most question on the test were similar to the lab exercises. Therefore, I finished the test for only 20 minutes.

This week in lecture we talked more about binary trees, specifically binary search trees. A binary search tree (BST) is similar to the binary tree I talked about two posts ago, except it has the extra condition that the data in the left subtree is less than the data in the root, which in turn is less than the data in the right subtree. This makes searching through the tree much more efficient, because we can use a binary search algorithm instead of a linear search algorithm. Recalling some information from CSC165, we know that binary search has runtime O(log n) whereas linear search takes O(n)–Binary search is much better, because the BST is already sorted, so it can ignore approximately half of the values, because they are all smaller/bigger than the value being searched for.

We also talked about deleting an element in a BST. To do this, we made a delete method in our BST class that simply calls a module-level function called _delete. If my understanding of wrapper classes from last week is correct, BST class function is acting as a wrapper for the module-level delete function, which does most of the work. The module-level function has many cases to deal with. It is given a node in a BST and data to delete. If the node is not None, it can look for the data in the left subtree if the data is less than the node’s data, and the right subtree if it is greater, using the definition of a binary search tree. It then uses recursion to get down to a base case, where the node’s data is equal to the data being searched for. It returns a new tree with the appropriate data deleted.

def delete(node, data):

''' (BTNode, data) -> BTNode

Delete, if it exists, node with data and return resulting tree.

>>> b = BTNode(8)

>>> b = insert(b, 4)

>>> b = insert(b, 2)

>>> b = insert(b, 6)

>>> b = insert(b, 12)

>>> b = insert(b, 14)

>>> b = insert(b, 10)

>>> b = delete(b, 12)

>>> print(b)

14

10

8

6

4

2

<BLANKLINE>

if node is None:

pass

elif node.data > data:

node.left = delete(node.left, data)

elif node.data < data:

node.right = delete(node.right, data)

elif node.left is None:

return_node = node.right

elif node.right is None:

return_node = node.left

else:

node.data = _find_max(node.left).data

node.left = delete(node.left, node.data)

return return_node

Part2: Term Test 2

Term test 2 was held on Wednesday. Preparing for the test, I concentrated on lab exercises. I redid all the lab exercises and timed my self.

I was very happy that most question on the test were similar to the lab exercises. Therefore, I finished the test for only 20 minutes.

Sunday, March 8, 2015

Impression of Week 8

We have been doing a lot of studying on linked lists recently, so I decided that’s what my topic will be this week.Linked lists are sort of like trees, which I mentioned last week. The difference being that linked list nodes only have one child each, resulting in a straight line of data—a “list”.

>>> x = LinkedList(2, LinkedList(3, LinkedList(4)))

>>> str(x)

“2 -> 3 -> 4 -> None”

>>> x

2 -> 3 -> 4 -> None

In that example above, I performed a few lines on the LLNode function that was provided in lecture. I understood the point of objects pointing to another object and so forth.

The fundamental principle of BST's is that all the data in the left subtree is less than the root, and all the data in the right subtree is larger than the root. The implementation that was used was the wrapper approach (similar to linked list) in that there was a class for a BSTNode and a class for the whole BST. Throughout the lectures for the week we worked through coding common methods such as insert and delete, using recursion. Danny also showed us the significance of helper functions, which made the coding a lot easier too see.

It was saying that whatever value is at the start of the BST will be the root, and it iterates over the values afterwards. So if I say [5, 3, 6, 7], 5 will be the node, 3 will be the left branch and 6 will be the right branch, because 3 is less than 5 and 6 is greater than 5. 7 will be placed on the right of 6. So in all this will be how it will look like on the python shell:

>>> x = LinkedList(2, LinkedList(3, LinkedList(4)))

>>> str(x)

“2 -> 3 -> 4 -> None”

>>> x

2 -> 3 -> 4 -> None

In that example above, I performed a few lines on the LLNode function that was provided in lecture. I understood the point of objects pointing to another object and so forth.

The fundamental principle of BST's is that all the data in the left subtree is less than the root, and all the data in the right subtree is larger than the root. The implementation that was used was the wrapper approach (similar to linked list) in that there was a class for a BSTNode and a class for the whole BST. Throughout the lectures for the week we worked through coding common methods such as insert and delete, using recursion. Danny also showed us the significance of helper functions, which made the coding a lot easier too see.

>>> x = BST([5, 3, 6, 7])

>>> print(x)

7

6

5

3

It was saying that whatever value is at the start of the BST will be the root, and it iterates over the values afterwards. So if I say [5, 3, 6, 7], 5 will be the node, 3 will be the left branch and 6 will be the right branch, because 3 is less than 5 and 6 is greater than 5. 7 will be placed on the right of 6. So in all this will be how it will look like on the python shell:

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Summary of Recursion-Week 7

Recursion is a method of solving problems that involves breaking a problem down into smaller and smaller subproblems until you get to a small enough problem that it can be solved trivially. Usually recursion involves a function calling itself. While it may not seem like much on the surface, recursion allows us to write elegant solutions to problems that may otherwise be very difficult to program.

A base case is the part of a recursive function where it doesn't call itself. Designing a recursive function requires that you carefully choose a base case and make sure that every sequence of function calls eventually reaches a base case.

example: Calculating the Sum of a List of Numbers

def listsum(numList):

if len(numList) == 1:

return numList[0]

else:

return numList[0] + listsum(numList[1:])

How would I compute the sum of a list of numbers? If I were a mathematician,I might start by recalling that addition is a function that is defined for two parameters, a pair of numbers. To redefine the problem from adding a list to adding pairs of numbers, I could rewrite the list as a fully parenthesized expression. Such an expression looks like this:

total= (1+(3+(5+(7+9))))total= (1+(3+(5+16)))total= (1+(3+21))total= (1+24)total= 25

listSum(numList)=first(numList)+listSum(rest(numList))

A base case is the part of a recursive function where it doesn't call itself. Designing a recursive function requires that you carefully choose a base case and make sure that every sequence of function calls eventually reaches a base case.

example: Calculating the Sum of a List of Numbers

def listsum(numList):

if len(numList) == 1:

return numList[0]

else:

return numList[0] + listsum(numList[1:])

How would I compute the sum of a list of numbers? If I were a mathematician,I might start by recalling that addition is a function that is defined for two parameters, a pair of numbers. To redefine the problem from adding a list to adding pairs of numbers, I could rewrite the list as a fully parenthesized expression. Such an expression looks like this:

total= (1+(3+(5+(7+9))))total= (1+(3+(5+16)))total= (1+(3+21))total= (1+24)total= 25

listSum(numList)=first(numList)+listSum(rest(numList))

In this equation first(numList) returns the first element of the list and rest(numList) returns a list of everything but the first element.

all recursive algorithms must obey three important laws:

- A recursive algorithm must have a base case.

- A recursive algorithm must change its state and move toward the base case.

- A recursive algorithm must call itself, recursively.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)